Environmental Impact

Environmental Impact: Land, Greenhouse Gas, Water, and Pollution of Grass-Finished vs Grass-Fed

The environmental and economic impacts of grass-finished vs. grain-finished beef are complex and involve trade-offs. It’s not a simple case of one being unequivocally “better” in all aspects.

This is where the debate often gets heated, with valid points on both sides.

Grass-Finished Beef:

Land Use:

Higher Land Footprint per Kg of Meat: Grass-finished cattle grow slower and require more land per animal over their lifespan to reach market weight. This means that to produce the same amount of beef, grass-finished systems generally require significantly more acreage than grain-finished systems. This can be a concern regarding deforestation or conversion of valuable ecosystems into pastureland, especially if not managed sustainably.

Potential for Regenerative Land Management: When managed using practices like rotational grazing or regenerative agriculture, grass-finished systems can offer substantial environmental benefits:

Soil Health: Grazing animals can improve soil structure, water infiltration, and nutrient cycling, reducing erosion and increasing soil organic matter.

Carbon Sequestration: Healthy, well-managed pastures can act as carbon sinks, drawing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it in the soil. This is a key argument for the environmental benefits of grass-finished beef, though the net carbon benefit is a subject of ongoing scientific debate, as some studies suggest the methane emissions can outweigh sequestration.

Biodiversity: Diverse pastures support a wider range of plant species, insects, and wildlife, contributing to overall ecosystem health.

Reduced Chemical Inputs: Grass-finished systems typically rely less on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides compared to conventional grain production, reducing chemical runoff into waterways.

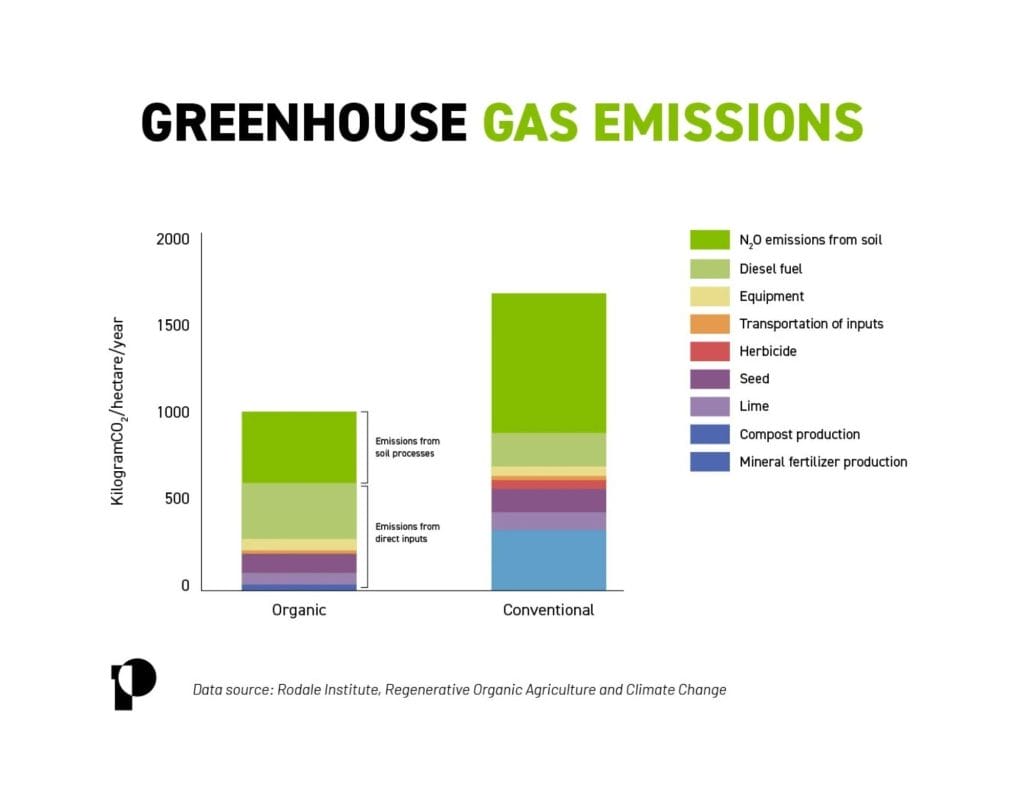

Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGs):

Methane (CH4) from Enteric Fermentation: All cattle produce methane through their digestive process (enteric fermentation). Because grass-finished cattle take longer to reach market weight, they may produce more methane over their lifespan compared to faster-growing grain-finished cattle.

Nitrous Oxide (N2O): While typically lower than grain-based systems due to less synthetic fertilizer use, poorly managed manure on pastures can still lead to N2O emissions.

Carbon Sequestration Offset (Debated): The ability of well-managed grasslands to sequester carbon is a significant factor. However, studies vary widely on whether this sequestration is sufficient to offset the methane emissions, or if it makes grass-finished beef more carbon intensive per unit of protein than grain-finished beef. Recent research, for example, has suggested that US grass-fed beef may be as carbon-intensive or even more carbon-intensive than industrial beef, particularly when considering the “carbon opportunity cost” of land used for grazing instead of other carbon-sequestering uses.

Water Use:

“Green Water” vs. “Blue Water”: Grass-finished systems primarily rely on “green water” (rainfall stored in the soil), which is generally considered to have a lower environmental impact than “blue water” (irrigation from rivers, lakes, or groundwater).

Reduced Irrigation Needs: There’s no need to irrigate vast fields of corn or soy for feed.

Improved Water Retention: Healthy, regeneratively managed pastures improve the soil’s ability to absorb and retain water, reducing runoff and improving local water cycles.

Pollution:

Reduced Water Pollution: Without concentrated manure in feedlots, the risk of nutrient runoff (nitrogen, phosphorus) into waterways is significantly lower, which can mitigate issues like algal blooms and dead zones.

Less Air Pollution: Fewer concentrated animal emissions (ammonia, dust) compared to large feedlots.

Grain-Finished (Feedlot) Beef:

Land Use:

Lower Land Footprint for Finishing: Feedlots themselves occupy a relatively small area per animal.

High Indirect Land Use (Cropland): However, the vast majority of the land footprint for grain-finished beef comes from the land required to grow the corn, soy, and other grains that cattle consume. This often involves large-scale monoculture ranching, which can lead to:

Soil Degradation: Reduced soil organic matter, erosion, and compaction.

Habitat Loss/Deforestation: Conversion of natural habitats to cropland.

Reduced Biodiversity: Monoculture fields support less biodiversity than diverse pastures.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGs):

Methane (CH4): While feedlot cattle finish faster, their high-energy diets can still contribute to significant methane emissions.

Nitrous Oxide (N2O): A major concern from the production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers used on feed crops. N2O is a powerful greenhouse gas.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2): Emissions from fossil fuels used in ranching equipment (tillage, planting, harvesting), fertilizer production, and transport of feed to feedlots.

Manure Management: Large amounts of concentrated manure in feedlots can release significant methane and nitrous oxide if not managed properly.

Water Use:

High “Blue Water” Footprint: Grain-finished beef has a higher “blue water” footprint due to the irrigation required for growing feed crops like corn and soy. This puts pressure on freshwater resources, especially in drought-prone regions.

Water Pollution: Runoff from fertilized fields (pesticides, herbicides, excess nutrients) can pollute rivers, lakes, and groundwater.

Pollution:

Concentrated Waste: The sheer volume of manure in feedlots can lead to severe localized air and water pollution if not properly managed, including odor issues, ammonia emissions, and nutrient runoff.

Environmental Summary: There are trade-offs. Grass-finished systems, when managed regeneratively, can offer benefits like carbon sequestration and improved biodiversity on pastureland, but they require more land and animals produce methane for longer. Grain-finished systems are more land-efficient in terms of direct animal housing but have a large indirect footprint from feed production, involving significant GHG emissions from fertilizer and machinery, and often greater water pollution. The scientific consensus on the net carbon footprint per unit of beef is still evolving and complex, with some studies suggesting grain-finished beef has a lower carbon footprint due to faster growth, while others highlight the benefits of well-managed grass systems.

The economics of grass-finished vs. grain-finished beef are vastly different, impacting producers, consumers, and the broader supply chain.

Grass-Finished Beef:

Higher Production Costs per Pound:

Slower Growth Rate: As cattle take longer to reach market weight, the cost of maintaining them for extended periods (feed, labor, land) increases per pound of meat produced.

Higher Land Requirements: More land is needed per animal, which can be a significant cost, especially in areas with high land values.

Labor Intensive: Managing rotational grazing and monitoring individual animals on pasture can be more labor-intensive than managing a feedlot.

Processing Challenges: The supply chain for grass-finished beef is often less developed. Smaller, specialized processing facilities may have higher per-animal costs, and finding available slots can be difficult.

Seasonal Variability: Production is more tied to natural cycles and forage availability, which can introduce seasonal variations in supply and cost.

Premium Pricing:

Consumer Demand: Growing consumer demand for “natural,” “sustainable,” and “humanely raised” products allows grass-finished beef to command a significant price premium over conventional beef. Consumers are often willing to pay more for perceived health, environmental, and ethical benefits.

Niche Market: It operates as a niche market, often through direct-to-consumer sales (ranchers’ markets, online stores, CSAs) or specialized retail outlets, which allows producers to capture a larger share of the retail dollar.

Profitability:

Potentially Higher Margins for Producers (per animal): While costs are higher, the price premium can allow producers to achieve higher profit margins per head compared to selling into the commodity grain-finished market.

Requires Different Business Model: Success often hinges on effective direct marketing, building strong customer relationships, and managing a more complex production schedule.

Barriers to Entry: The need for more land, specialized knowledge of pasture management, and direct marketing skills can be barriers for new producers.

Economic Resilience:

Reduced Reliance on External Inputs: Less dependence on volatile commodity markets for feed grains and synthetic fertilizers can make these operations more resilient to input price fluctuations.

Diversification: Ranchers can diversify their income by integrating other enterprises, like selling hay, or offering agritourism.

Grain-Finished (Feedlot) Beef:

Lower Production Costs per Pound (Typically):

Faster Growth Rate: Rapid weight gain on high-energy diets means animals reach market weight quickly, reducing the time and associated costs of housing and care.

Economies of Scale: Large-scale corporate feedlots benefit from significant economies of scale in purchasing feed, managing logistics, and processing.

Efficiency: Automated feeding systems and standardized management practices lead to high efficiency in converting feed into meat.

Established Supply Chain: A highly efficient and integrated supply chain for grain production, feed delivery, and large-scale slaughterhouses reduces costs.

Commodity Pricing:

Price Takers: Producers in this system typically sell into a commodity market where prices are largely determined by supply and demand dynamics, with little ability to command premiums.

Thin Margins (often): While highly efficient, profit margins per animal can be thin, relying on high volume to generate overall profitability.

Market Dominance:

Meets Mass Market Demand: This system is designed to produce large quantities of consistent beef at a relatively low price, meeting the demand of the vast majority of consumers and foodservice industries.

Less Direct Consumer Interaction: Producers generally sell to large packers, with less direct interaction with the end consumer.

Economic Vulnerabilities:

Input Price Volatility: Highly dependent on the price of corn, soy, and other feed grains, which can fluctuate significantly due to weather, global markets, and energy prices.

Environmental Regulations: Increasing environmental regulations related to manure management and emissions can add compliance costs.

Disease Outbreaks: Close confinement can make feedlots vulnerable to rapid spread of disease, potentially leading to significant losses and increased medication costs.

Economic Summary: Grain-finished beef dominates the market due to its efficiency in producing high volumes at lower per-pound costs, benefiting from economies of scale and an established supply chain. However, producers often face thin margins and are vulnerable to feed price volatility. Grass-finished beef has higher production costs per pound but can command premium prices due to growing consumer demand, offering potentially higher profit margins per animal for producers willing to operate within a niche market and manage a different business model.

In summary: If you are seeking beef from cattle that have lived their entire lives on a forage-only diet, look for labels that explicitly state “grass-finished” or “100% grass-fed.” Certifications from organizations like the Audubon Conservation Ranching can provide further assurance of adherence to strict forage-only and pasture-raised standards.

The Industrial Meat Supply Chain vs Supporting your local rancher

How Feedlot Beef Ends Up in Retail: The Industrial Meat Supply Chain

The path from a feedlot to your grocery store shelf is highly industrialized and designed for efficiency and volume.

Feedlots to Packing Plants: Once cattle in feedlots reach their target market weight (typically around 1,200-1,500 lbs and 18-24 months old), they are transported to large, centralized packing (slaughter) plants. These plants are often strategically located near major feedlot regions.

High-Volume Slaughter and Disassembly: Packing plants are massive operations designed to process thousands of animals daily. The process is highly streamlined:

Stunning and Bleeding: Animals are stunned to render them unconscious before bleeding typically in front of the whole herd, leading to stress and fear.

Skinning and Evisceration: The hide is removed, and internal organs are removed and inspected.

Halving and Quartering: The carcass is typically split in half, then into quarters (forequarter and hindquarter).

De-boning and Primal Cuts: Skilled butchers (or increasingly, automated systems) break down the quarters into “primal cuts” (e.g., chuck, rib, loin, round).

Further Processing and “Value-Added” Products:

Boxed Beef: The primal cuts are often vacuum-sealed and shipped in boxes to retailers or further processing facilities. This “boxed beef” system was revolutionary in reducing shipping weight and increasing efficiency.

Trimmings and Leftovers: During the butchering process, there are inevitably smaller pieces of meat and fat that are trimmed off the larger primal cuts. These trimmings are where “meat glue” and “pink slime” come into play. They are considered valuable by-products in a system focused on maximizing yield from each carcass.

Grinding and Blending: For ground beef, various trimmings from all animals are combined and ground, sometimes over 1000 animals in 1 batch of ground beef. This is where different lean-to-fat ratios are achieved, and where practices like “pink slime” might be incorporated.

Distribution to Retail: The processed beef products are then shipped via refrigerated trucks to regional distribution centers and ultimately to individual grocery stores, restaurants, and other food service outlets.

Potentially Harmful Cost-Saving Practices:

In the quest for efficiency and maximizing yield, certain practices have emerged in the industrial beef supply chain that have raised consumer concerns, often due to their perceived “unnaturalness” or potential food safety implications.

“Meat Glue” (Transglutaminase – TG):

What it is: Transglutaminase (TG) is an enzyme, often referred to as “meat glue.” It has the ability to form strong bonds between proteins. It’s found naturally in humans, animals, and plants, and the version used in food is typically derived from bacterial fermentation or animal blood plasma (e.g., from pigs or cows).

How it’s used: TG is used to bind together smaller, less valuable pieces of meat (trimmings, scraps) into what appears to be a larger, solid cut of meat, like a steak or roast. For example, it can take several small beef tenderloin pieces and “glue” them into one large “formed” tenderloin, which can then be sold at a higher price than the individual scraps.

Why it’s used (Cost-Saving): It allows processors to utilize cuts that would otherwise be relegated to ground beef or discarded, thus increasing the marketable yield and profitability from each animal. It makes otherwise “waste” product more valuable.

Consumer Concerns & Potential Harms:

Deception: The primary concern for consumers is deception. A “formed” steak looks identical to a whole-muscle steak, but consumers are often unaware of the difference and may pay a premium for what they believe is a single, higher-quality cut.

Increased Bacterial Contamination Risk: This is the most significant food safety concern. When meat is cut, bacteria (like E. coli or Salmonella) that are normally only on the surface of a whole muscle cut can be introduced to the interior when pieces are glued together. If a whole steak has surface bacteria, cooking the exterior thoroughly usually kills them. With a “glued” steak, bacteria can be on the inside where it might not reach high enough temperatures to be killed, especially if cooked rare or medium-rare.

Allergies/Sensitivities: Some sources suggest potential issues for individuals with gluten sensitivities or celiac disease, though this is less widely established than the bacterial risk.

Regulation: In the U.S., the FDA considers transglutaminase “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS). However, the USDA requires that products containing it be labeled to indicate they are “formed” or “reformed” meat products (e.g., “Formed Beef Tenderloin”) to prevent consumer deception. The European Union has banned its use in meat products for similar reasons (deception and food safety).

“Pink Slime” (Lean Finely Textured Beef – LFTB):

What it is: “Pink slime” is the colloquial term for Lean Finely Textured Beef (LFTB). It’s a product made from beef trimmings (small pieces of meat and fat that are difficult to separate from bones during butchering). These trimmings are heated to separate the lean meat from the fat, then spun in a centrifuge. The resulting lean product is finely textured and often treated with ammonium hydroxide gas or citric acid to kill bacteria like E. coli and Salmonella.

How it’s used: LFTB is mixed into ground beef, typically to increase the lean content and to maximize the utilization of the entire carcass.

Why it’s used (Cost-Saving): It’s a very cost-effective way to produce lean ground beef from otherwise less desirable or difficult-to-process trimmings, preventing waste and increasing profitability.

Consumer Concerns & Potential Harms:

Perception of “Not Real Meat”: The “pink slime” moniker, popularized by media reports, created a strong negative public perception that it was an unappetizing, unnatural filler rather than “real beef.”

Ammonia Treatment: The use of ammonium hydroxide, while approved by the FDA as safe and used in other food products, raised concerns for consumers who were uncomfortable with chemicals being used on their meat.

Food Safety (Context): Proponents argued that the ammonia treatment actually improved food safety by reducing pathogens. Opponents argued that the need for such treatment indicated an inherent issue with the source material’s cleanliness or processing methods.

Regulation & Market Impact: LFTB is considered safe and is regulated by the USDA. However, due to public outcry and negative perception, its use in ground beef by major retailers and fast-food chains significantly declined in the 2010s. While still technically permitted and sometimes used, it’s far less common in retail ground beef than it once was.

The Contrast: Purchasing from a Local Rancher (Single Animal, No Tricks)

When you purchase beef directly from a local rancher, especially one raising grass-finished cattle and selling by the quarter, half, or whole animal (or even individual cuts from a known animal), you typically bypass these industrial practices entirely.

Single Animal Source: The beef you receive comes from one specific animal that you can often learn about (its breed, age, how it was raised). There’s no mixing of meat from hundreds or thousands of different animals.

Whole Muscle Integrity: You are buying primal cuts or sub-primal cuts directly from the animal. There’s no need to “glue” together scraps because the focus is on utilizing the natural cuts of the animal. If you get ground beef, it’s typically made from trimmings of that same animal, not a blend of various sources or LFTB.

Transparency and Trust:

Knowing the Producer: You can often visit the ranch, see the conditions, and speak directly with the rancher about their practices (diet, animal welfare, processing). This builds a level of trust that is impossible with large-scale industrial operations.

Direct Butchering: The animal is typically processed at a smaller, local abattoir. While these abattoirs follow regulations, their scale and direct relationship with the rancher mean less incentive or opportunity for “tricks.” Cuts are generally what they appear to be.

No Unwanted Additives: Local ranchers selling whole cuts or custom-ground beef are highly unlikely to use “meat glue” or “pink slime.” Their business model relies on the inherent quality and integrity of their product, not on maximizing yield from low-value scraps.

No “Butchering Tricks”: The cuts you receive are straightforward. A steak is a steak from a single muscle. Ground beef is simply ground beef from the trimmings of that animal. There’s no complex restructuring or blending with treated by-products.

Flavor and Texture: While “tricks” might improve the visual consistency of industrial products, a local, single-animal source often offers superior and more unique flavor and texture, characteristic of its breed and diet.

In essence, the industrial feedlot-to-retail model, while efficient and providing affordable meat, creates conditions and incentives for practices like “meat glue” and “pink slime” to maximize profit from every part of the carcass. These practices raise concerns about transparency, potential food safety (especially with meat glue), and consumer perception. In contrast, purchasing directly from a local rancher provides a much more transparent supply chain, typically involving beef from a single animal, without the use of such controversial processing techniques.